It’s easy to ignore the United Nations and World Bank pontificators as Über-leftists and global climate change fanatics. However, of value to us ordinary peeps, is a recognition that U.N and WB outlooks permeate the World Economic Forum and Davos groups.

The multinational corporations and quasi-governmental entities in/around the World Economic Forum (WEF) are the people who call themselves “elites” and shape global policy. As a result, when the U.N. and Word Bank start talking about widespread global famine as a result of energy policy impacts to the farming industry, specifically natural gas costs and fertilizer resulting in lower crop yields, it is worth paying attention.

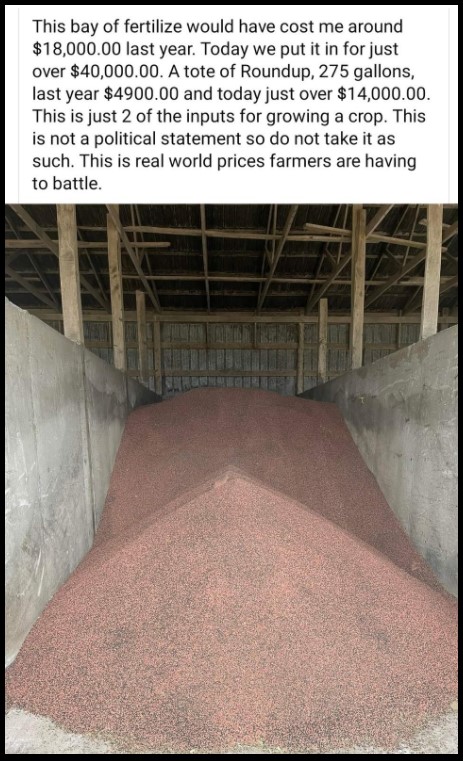

We have already discussed the U.S. impact from higher fertilizer costs HERE. As a nation we are blessed and fortunate to be living on land that is naturally healthy and fertile enough to grow food in abundance. However, if our crop yields drop our export ability diminishes. The world relies on the U.S. as a food basket. You might have recently heard about foreign countries buying up U.S. farmland? Well….

In this outline from the Wall Street Journal, they note those increased costs mean less crops in all continents especially the third world regions. That can be catastrophic for nations that already have food insecurity issues.

(Via Wall Street Journal) Christina Ribeiro do Valle, who comes from a long line of coffee growers in Brazil, is this year paying three times what she paid last year for the fertilizer she needs. Coupled with a recent drought that hit her crop hard, it means Ms. do Valle, 75, will produce a fraction of her Ribeiro do Valle brand of coffee, some of which is exported.

There is also a shortage of fertilizer. “This year, you pay, then put your name on a waiting list, and the supplier delivers it when he has it,” she said.

[…] Farmers in the U.S. are also feeling the pinch, with some shifting their planting plans. But the impact is expected to be worse in developing countries where smallholders have limited access to bank loans and can’t pay up front for expensive fertilizer.

Fertilizer demand in sub-Saharan Africa could fall 30% in 2022, according to the International Fertilizer Development Center, a global nonprofit organization. That would translate to 30 million metric tons less food produced, which the center says is equivalent to the food needs of 100 million people.

“Lower fertilizer use will inevitably weigh on food production and quality, affecting food availability, rural incomes and the livelihoods of the poor,” said Josef Schmidhuber, deputy director of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s trade and markets division.

As the pandemic enters year three, more households are having to cut down on the quantity and quality of food they consume, the World Bank said in a note last month, noting that high fertilizer prices were adding to costs. Around 2.4 billion people lacked access to adequate food in 2020, up 320 million from the year before, it said. Inflation rose in about 80% of emerging-market economies last year, with roughly a third seeing double-digit food inflation, according to the World Bank.

Diammonium phosphate, or DAP, a commonly used phosphate fertilizer, cost $745 per metric ton in December—more than double its 2020 average price. December prices for Eastern European urea, a widely exported nitrogen fertilizer, were nearly four times the 2020 average.

[…] Tony Will, chief executive of CF Industries Holdings Inc., a leading nitrogen fertilizer manufacturer based in Deerfield, Ill., said he expected lower fertilization levels this year to result in reduced agricultural yields. The company has only reopened one of the two U.K. plants it closed in September, citing high natural-gas prices and low availability of truck drivers. Plants in North America, where gas prices are lower, are running at maximum capacity, Mr. Will said.

Industry experts say European production is likely to be constrained as long as natural-gas prices remain high there, with shortages in parts of the developing world amplified by trade restrictions in other major fertilizer exporters. (read more)

Leftism has consequences. Chase the surfacing issue back to its origin, and you will find the climate change agenda at the heart of changes in energy policy. The changes in energy policy, as noted above, have consequences like higher prices. Those higher prices for natural gas, oil, fuel, etc mean higher prices for fertilizer… which leads to less food.

Chasing the climate change agenda actually kills people. Then again, from the perspective of the climate change cult, less people are not a bad thing.

As we have shared…. “The absence of food will most certainly change things.”

[ GO DEEP ]

I still remember that in the old days they used cow crap.

When I was i stationed on a temporary duty in Fairford, England

I watched a farmer using a tractor and a machine to fling it all over his field

before tilling it in.

So yeah, we need to get back to the basics. Chemicals just make it easier and means a little

less work.

Still doing that all over PA.

In Minnesota, too.

It’s called the Smell of Money.

Portland too…

And San Fran and so on…

True that: Both those towns have bumper crops of urban nomads.

The EPA has rules on that.

EPA can take a hike

When I was a kid growing up in Georgia, my grandad raised chickens by the hundreds in large, long chicken houses. After the trucks took the chickens away to market, we shoveled all the chicken poop into spreaders that we used to fertilize grandad’s crops.

My Dad used chicken poop to fertilize our small garden and lawn. It worked like magic but it sure did stink.

Best natural fertilizer to use since chicken sh@t has a great balance of NPK nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium.

Best for tomatoes.

Farm I lived on in New Paltz NY did the same thing. Chicken shit was /is a powerful nitrate.

Washington DC has a massive supply of crap, they are called lawmakers.

Funny you should say that.

My brother in law spreads fertilizer sourced from Municipal Waste Treatment facilities on farms in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

From the company website….

There is no waste in nature, only fuel for other living things.

https://www.synagro.com/

Lots of people take lots of pharmaceuticals, and it partly comes out in their waste which is going into the Municipal Waste Treatment facilities… If you think that waste has some how been purified and free of those drugs? rofl… OK… enjoy.

There’s speculation that seasonal use of human waste as fertilizer (bc it aerosolizes) here and abroad is contributing to the spread of Covid. (Hint: hunters aren’t spreading Covid to deer.) See @EthicalSceptic twitter

That’s why you read about samples being taken from waste facilities to determine if and how much Covid is in an area.

The Chinese just announced they’re switching to rectal swabs for covid detection.

If ANYONE knows anything about covid, it’s the people who created it and unleashed it on the world.

Correct.

Human waste is completely different from animal waste and should never, ever re-enter the food chain.

It is highly toxic.

Human poop?????? yuck!

It’s been broken down and sterilized somewhat. They use it here in Oklahoma also. And really, until you are in farming you don’t know what all goes on. Anhydrous ammonia is a deadly poison, a gas, manufactured from natural gas in a refinery. It’s put into the soil for fertilizer in these farms all across the country.

To me, I’d rather have sterilized human waste for many reasons. One, it’s putting back in the soil not robbing and two, it’s out doing what poop was meant to do not being dumped into our rivers and lakes because that’s exactly what they do with it.

Anhydrous comes from the oil industry and they pollute with noise, smells, all sorts of exhaust stacks. We have an anhydrous plant by my house and when it starts to rain, they belch some really nasty toxic stuff in the air.

The smell of the sewer plant is disgusting but a refinery is worse, IMHO.

Im not against the oil industry I’d just like to see true use of renewable resources. This green energy push is a joke, a money scheme and it’s obvious.

Where does plastic for bottles come from? Tells you all you need to know about green energy.

My fellow geezers likely remember Milorganite, one of the first mass-marketed bagged fertilizers made from municipal sewer sludge.

It’s time to watch Soylent Green again. Circa 1973. Takes place in the year 2022.

yup but their “crap” is pure unadulterated poison.

We the people need to use sling-blades to start cutting out the weeds and put in new plants…

This “climate change” BS has gone on long enough, since 1970’s and it’s about time to get rid of it…

The HOW is up to us as a whole!!!!!!!

Fertilizer and insecticides have increased the amount of food per acre exponentially. It’s what permits use to feed so many people here and abroad.

I don’t think it’s as simple as just going back to manure.

Manure is basically a nitrogen source. There are a lot more elements beside nitrogen which goes into growing a crop.

Of course. And there is only so much poop available. That’s where synthesized products come into play when millions of acres are being farmed. Petroleum and natural gas are the feedstocks for most modern agricultural chemicals. The first, true Green Revolution was started by pioneers like Norman Borlaug who helped develop disease resistant, high yield crops.

We can’t go back to the good old days and expect to feed hundreds of millions of people. Modern communist “Greenies” would solve the problem by reducing the earth’s population (starvation, ‘vaccines’, war). Borlaug proved the logical, altruistic solution was to get more food out of each acre. We are nowhere near “peak” food production. But with idiots running the world there’s no telling how bad things will get.

John, your summary of how farmers can best fertilize their fields is absolute nonsense. It only makes sense if you work in the marketing department of Bayer or Monsanto. Commercial fertilizers became popular after World War II when chemical companies making explosive chemicals for the military wanted to find a market for their chemicals after the war ended. Read “The one-straw revolution : an introduction to natural farming” by Fukuoka if you want a demonstration that natural input farming produces more and better quality food than chemical fertilizer in a bag. Then, get a few chickens and start your garden. Those with victory gardens will have a better chance of eating during the next decade.

“Old school” farming techniques are romantic and suitable for home gardens, hobby farms, etc. However, they are not efficient enough to support the population of the world today, and the subsequent demand for US-produced agriculture staples (corn, wheat, soy, etc). It’s not a matter of advocating for Monsanto or not — the truth of this is in the numbers, which are available from any number of sources.

Post WW2 productivity due to modern fertilizer, equipment, and techniques/methods are required if we’re to maintain and feed the world, unless significantly more arable land (and significantly more people) are to be involved in farming — and unfortunately both those resources are finite.

Personally I’m all for letting Africa and the world starve to death while sealing off our borders, but I suspect most aren’t.

I don’t want the world to starve, BUT when did it become our responsibility to feed the world? Each country should be doing their jobs. If Gates and Monsanto had not interfered across the globe, I suspect people of the world had historical knowledge of how to survive. Although, they claim they’ve saved millions of people, I have different viewpoint. How about we tend to our own ‘taters? How about the government get out of the business of farming and ranching and let people do what they do best? How about they leave everyone the hell alone?

.02

I’d love nothing more than just that.

The Middle East, Africa, and much of Asia have massive populations directly due to modern farming and/or the productivity of American farmers (and others in the west). These populations are far out of scope and scale to what otherwise would be naturally supportable. Modern (western) ag abundance has acclimated the population of the world to 1) cheap food (here in the US and to a lesser extent other western countries), and/or 2) food access well beyond what could be supported naturally.

Something has to give, snd it ought not to be our problem — though “we” / our elites have made it so. To be honest, things may get to a point in some of the poorer countries that there become major nutritional crises and mass migrations. The bad news for us is that right now the Biden Regime is still in control, and any flood of “refugees” will be allowed in to further destroy traditional America and traditional American peoples.

Fubar aka military…..if we deported all illegals and spread the population out instead of bowing to the 1% and squeezing people into huge urbanized mega metropolises and had 2 acres and a mule ideology again we’d be fine….smart cities, I0T of bodies, chip implants embedded in brains ….we’d all be better off without the elite bankers Blackrock and Vanguard trying to tag the world population as if we were their cattle …but you already know that….the nwo enslavement of humanity for 1% of the population ….the most filthy people on the planet ….

In Christ We Win

Can I show you graphs on how productive the vaccine is? My point is “where is the money” it’s been coming from and for big oil for decades. I have seen farms using other fertilizers and products and do better over time because of soil quality.

Farmers would use more of these techniques but they are not as easy to get and quantity is a factor. Because of the ‘big money’ chemicals are cheaper than products that break down and are good for the soil.

Farmers can’t afford the difference, and the products are expensive and harder to find.

Another issue is, farmers are told what to use on these big farms, there is no choice.

I say again, the problem is not food production, the problem is 40% of all food is lost between the farm and the plate. I am really pro-beef, but corn and soybeans are for two industries, 1. the Feed Yards, 2 Ethanol -Fuel. The solution to the fertilizer problem is soil health, the solution to the drought problems is soil health, the solution to the health crisis is soil health, (USDA data, the nutritional value of our food has decreased every year for over 50 years) but it does not support the greed agenda. The farmer “needs” our fertilizer every year. Take a pill for your symptoms, “every day”. There is no desire to fix the problems. There is a great desire for you to spend your dollars every day.

Factory farms and thousands of acres of monoculture are not sustainable. It was attempted in the collectivized farms in the USSR. The best bet is de-regulation of the small farmer so they can make money, instead of subsidizing huge industrial “farms”. Millions of small farms can feed the country, and provide a living for those doing it. When the USSR fell, I read that the food supply came from millions of small backyard gardens. Smaller diversified farms are less polluting, more sustainable

Another gullible, naïve yokel without a clue. I was raised on a small farm and I owned and operated what you would call large farm. You have zero idea what it is all about and I mean zero.

The comments on this thread are so ridiculous, I give up. Just like the people who think packaged meat “comes from” the grocery store, most are woefully ignorant about crop farming.

It would take a fabulous Sundance-style exposé, for people to fully understand the complexities. It is not like home-gardening on a much larger scale.

Many folks actually believe that all the corn and beans we grow, are for human consumption. Like Del Monte vegetables, for example. Where to start?

But you see, we’re not going back to what was. We’re past the tipping point. They broke it to destroy it; there will not be the numbers of people left alive to feed. Nations will be blockaded, Cargo planes won’t be safe in the air or on the Tarmac. We won’t be selling food to our enemies enemy. We will learn how to individually compost and grow even one vegetable or fruit, or eggs, something in abundance, and trade some for variety and nutrition. We are a long way (years) out from reversing 2 years of deliberate damage, but some can survive.

Hand tools won’t require petroleum, tractors will rust; who will deliver a crop on an E-vehicle to the processors, to the Sellers? Who will transport food when logs are thrown on the road and drivers pulled from cabs? Recall Haiti? Gangs of young men stole the donated food enroute. No we won’t be feeding nations. People understand stores but not farming. But yes, individuals will be mastering Victory gardens because we did it before during WW II. People will learn to compost, trade seeds, eat seasonally, can, dehydrate and pray more. But this time we’re not a nation united against an enemy, we’re divided by the enemy.

You may be angry because you know most don’t understand the scope of big farms nor do they have a garden space, or can’t physically garden; go back to your beginnings and teach them how you began an Ag life. We have tractors but won’t buy more because mechanical equipment takes petroleum and E-tractors and trucks are too expensive because they’re investment tools for Congress who is destroying the petroleum competition.

Necessity will teach 330 million how to farm by hand or starve. I will be inventorying tools, buying what I need, composting from the heap lined next to the gardens, eating from a Victory Garden, a nut tree and fruit trees and berries, canning and trading surplus. If… Biden stops pushing for a nuclear war to protect Obama’s Ukrainian puppet govt.

You will be more valuable alive, teaching basics, guiding the hope-less. I have Ag Science degrees, live on a farm, we all have kitchen gardens because we love the soil, the weather, the work, the people, the always learning about God part.

I visited Russia in 1995; the period of their BBB just beginning. Few had refrigerators; two in 300 apts. had one though every apt. and house had electricity; a single electrical socket, one to a house wired to the center of the house ceiling, cords connected dropped down to a small radio, tv. No appliances. Housekeeping appliances and power tools couldn’t project Stalin’s voice throughout a huge nation. Refrigerators fell into that category, besides there wasn’t enough food to fill them. Picking plants and eggs daily and eating them daily saved the steel to make trains and cars for the govt.

Laundry washed in sinks and tubs and buckets. Stores that had meat at all showcased it without refrigeration. A foot from the bras. Breads were gone by 9:00am. Lines started early, if nothing you needed was left by your turn you bought what you didn’t need and traded it later. Gangs of 30-50 children beat the lone person for their shoes and coat and money. New money was printed every other month. When we left 3 weeks later we could not exchange ours at the airport for USD’s; it was no longer “in print”. We couldn’t even give it to the masses of elderly beggars with drastically swollen legs and feet that lined the streets.

The Translator explained all of the food was shipped in from Europe. The people were beaten down, so discouraged, and those who didn’t work also ate (equality), that the people made alcohol from backyard plants of corn, potatoes, wild berries, and drank instead. When they’d farmed the govt. came and collected their harvest and sold it and kept the money. Wives were abused by drunk husbands; abortions were birth control, because they couldn’t feed the child. Three or five abortions by married couples was not uncommon. Natural birth control is impervious to a drunk husband. Pills and prevention alternatives weren’t available. Parents locked their children out of the room while the parents ate. They gleaned wild foods in the forests, planted ‘garbage’ (onion tops, eyes of potatoes, squash seeds, etc.) Chickens were for eggs not meat. A cow was for milk not meat. In 1995 I watched horses, not tractors, pull wooden wagons in a wheat harvest and old men carrying old metal 5 gal (10#’s to the gallon !) milk jugs on wooded racks on their backs, walking long roads into towns to trade.

Outside of cities every house had a table on the street in front. The family waited in the sun for cars to drive by. To buy their lamps (no electricity), dishes (no food) a dining chair (no food for the table…) They had nothing else to do. This was the new economy of the Govt. / parent, no longer wants the job; feed yourself. No cars passed ours for 30 min. (no money for gasoline, no cars) the hours of an operating gas station determined your journey.

From destruction to Build Back Better was +/- 70 years, because the communist govt. bludgeoned the people to be children under tyrannical ‘parents’ who would care for them cradle to grave. The children without purpose, who could not think for themselves, who feared everything, who became alcoholics, missed being on the receiving side of the industrial age. We saw 50 gal black drums on the streets with a spigot and a dirty cup on a chain. Stills in the open on the streets. Beneath were the fires converting the corn to alcohol. Pay and drink on the go. Mental survival.

Only the govt. received. Only the people gave.

Cars for the ‘parents’, weaponry, military, railroads, roads and bridges, concrete by the mile consumed what little nourishment the ‘children’ scavenged. I saw no Victory backyard gardens. They were exhausted rebuilding. They could only line up each every morning at every store. Waiting for a share, dependency, was endemic.

Today it’s the Tech age, the AI age. Survivors today of this evil deception, this people hating campaign, this indifference to starvation, will not be allowed to return to the old ways of farming. They spent too much to control the food and farms for themselves. We saw that in Moscow around the palaces and Kremlin; the Mercedes Benz cars, the boutique shops with hand crafted shoes and French silks, the westernized restaurants and the hotel lobbies with a wall of shelves well stocked with endless liquor to purchase to take to your room. The Elites, the Parents, the Psychopathic and Narcissic all had money and titles. In 1995 a 4-5 star hotel room was $2700. to $5500. USD per night. Twenty six years ago.

Teach what you know while you can. Gather the hand tools. All this and more isn’t for nothing; they have a plan, we had none. There will be starvation AND survivors. And there is a God who already has solutions. You may be one.

I can’t fix the world, but I can try to raise as much food as I can for myself with my big garden and small flock of hens. I grow organically, for health reasons, and raise food for economic reasons, as I am an older, retired lady on a fixed income. If I need fewer resources from agri-business, that benefits those who don’t have the ability to raise their own food, more resources for them. I think the solution is more multifaceted than to only grow small and organic or only grow with chemicals on a factory farm. The world is a big place with billions of people living on it. Perhaps we should look at all the possible solutions, including less government interference.

John, Not really. They have sold us a bill of goods. Fertilizers, (synthetics) did allow us to push the yield higher but they have topped out. You can’t continue to add more fertilizer and get more yield. In addition, the synthetics (fertilizers and pesticides) are very heavy in salts and destroy the God-made microbiome in the soil. About 4 years ago we started doing 3 different types of soil tests on samples (MRI, CT Scan, and Xray – sort of). The average sample submitted across 22 states and over 1,000 samples using today’s NPK pricing show that the farms have over 4,000.00/acre of nutrients, but it will never release using Synthetics. It’s all about soil health. One more thing all of that corn and soybeans are good for the feed yards, ethanol, and world trade, Taxes associated every time it changes hands.

Chicken crap that is sterilized for mushroom farming is then sold off cheap, they can only use it once. It’s amazing stuff for your garden if you can lay your hands on it. Treat it like compost, but really potent compost. Doesn’t stink, well, too badly.

Sterilized is sterilized. Nothing is left alive to contribute life to a soil or any thing planted in it. It’s “potency” is not nutrients but as a soil conditioner creating a porous soil so fragile spores can ‘root’. Roots follow water but can’t in solid soils. Chicken’s, like the dirty eating bats, are meat eaters; bugs, worms; they eliminate the partially digested meat as “manure”. Partially digested is why the protein count is a shocking 16% – 22% – when collected/sourced. Back to, finished product sterilized is sterilized. The only safe manure is from cows, steers, sheep. It will build your compost pile and soil for years. Like a starter yeast in dough.

You need lots of cows. First

My grandmother was a good gardener. My mother told me that my grandmother used to work aged chicken litter into the rows where she intended to plant her onions. She used cow manure for the rest of the garden. The common wisdom was that chicken litter was “too hot” to be used for most of the other plants.

They don’t like cows any better than they do natural gas.

‘That aside, I lived next to a small slaughterhouse in a rural area of WA. The slaughterhouse had a blood truck. They collected the blood and spread it on the fields for fertilizer.

WOW… you might want to get a better UNDERSTANDING on what and how much cow crap would be needed. There aint enough cows to produce the needed “cow crap”.. Again.. the problem can be directly traced back to the scummy filthy lying climate douche bags… LIARS… EVERY SINGLE ONE OF THEM ARE LIARS.

cows fed hay or grazed on pastures (that also do best with fertilizer) sprayed with certain broadleaf weed killers will kill certain crop such as tomatoes, beans, peppers. Won’t harm others like corn, cucumbers, squash. Learned this the hard way with my aged horse manure compost. Took two years for my soil to return to the way it was.

The NIMBYs who move to rural areas to enjoy the view have a hissy fit about the smell.

I use compost cow crap and peat moss and my forty by twenty garden keeps us out of the produce department all year.

No, it means you must keep methane producing animals and that is undesirable to the CC crowd

A manure spreader. My Dad has one and they are still used on small farms in WNY.

I have an old New Idea (pronounced new-I-dee around here) manure spreader if anyone wants it. It was a good one in its day. Been stored in the barn.

anywhere close to Southeast Missouri?

Cows in feed lots generate lots of manure that is stored in huge lagoons. At appropriate times of year they pump it out over long hoses and chisel it into the ground in farm fields.

It’s call a manure spreader and the are STILL widely utilized across American Farms.

If AOC has HER way, the only cow manure you’ll be able to find will made out of rubber and imported from Hong Kong. In the meantime, we’ll all be eating rice cakes and soyburgers.

Retired Magistrate here: In the late 40’s through the 60’s my grandfather had a 90 acre dairy/corn farm in Scioto County, Ohio. He would take the manure from the dairy cows and put it in a manure spreader and use it to fertilize the corn crops.

I have pictures of my grandfather and myself standing in front of corn that was at least 10 feet tall with huge ears of corn. That was the only fertilizer he used and it grew great crops.

I understand with the mega farms this is no longer possible. However, back in the day that is what was used; nothing went to waste.

I imagine very little goes to waste now. Farmers work on a pretty thin margin.

What do you mean by “waste”? What has been going to “waste”?….and if so, where does a farmer put the “waste”?

The farmers in eastern NC used chicken manure. They liquefied it and sprayed it on the crops. It wasn’t pleasant on a hot humid day.

Yes, I grew up in a semi-rural area. If the wind blew a certain direction, you stayed inside due to the smell.

Hogs may smell worse than chickens.

Obviously one smells a dairy every time you drive by a dairy. To you it is a disgusting smell. To the dairyman it is the smell of money.

What do you think happens to all the manure produced on dairies go. It all goes on farmland. It is not a ” waste” piled somewhere. There is just not enough to provide the fertilizer needs for millions upon millions of farming acres.

Yep. Farmers put it on pastures that grows more grass for the cows to eat. The circle of life. Feed lots have farm operations that will take it. Nothing goes to waste. Almost 100% of it is already used. There is no extra for corn and soybean fields.

Plus, manure must be incorporated. It can’t just lie on top of the ground. Much of the corn around here is no-till because it is fuel efficient and prevents erosion. Chemical fertilizers leach into the soil from rain.

I know you know this stuff, but I am surprised what otherwise intelligent people do not know. Everyone that has grown a big garden thinks they know commercial farming. Yes, a garden is a good way to feed your family and I grow one. I don’t try to make a living doing it.

I doubt the EPA would allow that today.

Sure they would. The problem is there is not enough of it, it takes a lot more diesel fuel and time to collect and spread it. It is also not the exact analysis needed and the farmer still has to use chemical fertilizers to make up the difference.

Sorry this is not inside this topic but is GREAT news everyone should know:

@EpochTimes

·3h

#NewHampshire is poised to become the 1st US state to make #Ivermectin available as an over the counter medication and sanction it as a protected treatment for #COVID19, under a bill before the House Health, Human Services, and Elderly Affairs Committee.

Hopefully this will pass in time for people to benefit from it rather than get tied up in committee for a year or two. And from there? Maybe a Domino effect into other states?

Great news! Hopefully, other states will follow. Here in Texas, Ivermectin is readily available but requires a prescription. The wife takes it as a prophylactic. Anecdotal, but as a 70 year old, I’ve been in church w/o masks most Sundays for the last 20 months and no Rona. Im a few pounds over weight but in good health. I don’t know anyone in my immediate circle who has gotten very sick (save bro-in-laws sister who is over weight and a former smoker) or died from from this “dreaded disease.” Contagious yes, death with 4 or more co-morbidities yes, over half the deaths in nursing homes, yes. But this fear porn pandemic the government and the medical bureaucrats foisted upon us is sinister and a crime against humanity. Day one when we take back Congress, the vaccine and truth about Rona must be investigated. I’ll be telling my congressman’s and senators the same. DAY ONE!

No problem, we feed them bullets.

Balance will return.

At what point does this make the Green Climate-Change Crowd “GENOCIDAL MANIACS”.

And 30 million a year will be cross our border looking for a meal.

More likely that we will be crossing the border in a southbound direction.

Here it is. Soylent Green. https://gcn.com/emerging-tech/2021/11/darpa-seeks-top-chef-for-3d-printed-food/316299/

I’ll trade you three hecta-rations for your jar of strawberry jam!!!

Nothing important

I don’t think it’s going to affect supply much, but the prices of everything that crops are used for. Which is just about everything.

Two of the most corrupt organizations that should be completely eradicated from this earth because they are more to blame for where this world is right now.

Some of the Green Doom mongers expect millions at least to die in order to “save the planet.” The planet supersedes all other concerns in their radical frightened minds. The consequences of eliminating natural gas and other crucial energy sources is irrelevant to them. Reading the strict policies in the Green Manifestos of many Green parties in the world from the last decade to the present will prove that.

Sacrificing a billion or so people is not a serious concern to the most obsessed climate ideologues that believe they are on a “grand mission.” Unless their lives are threatened of course.

The Great Reset that actually happens may not be what the global elites had in mind

“Everything Old becomes new again and history repeats.”

China’s poisonous cancer causing GMO’s will one day be outlawed

all the bad cancer causing fertilizer chemicals will be banned

People will return to live off their land organically, provide healthy food for themselves.

Raise their children with godly values and a good work ethic

People will spend more time inventing and creating than on social media censorship platforms

Mom’s will go back to nurture and teach their own children

Public schools will return to the community in which they reside.

I can go on…. but i see a future where we’ll be on the right track again (MAGA) out of necessity and survival.

I hope i can live long enough to see it happen , i’ve prayed for such a day and Trump certainly has given all of humanity on this planet a trajectory shift that these communist globalists as hard as they try as crazy as they get they CAN NOT undo what Trump (one man) has been able to do for the future of humanity.

I’ve come to believe exactly the same.

Trump secretly would have liked to shut down all exports from China, and force manufacturing back to America. Now they’re doing it to themselves.

The BBB clan are going to make life hell, but oddly this dramatically accelerates requiring conservative America First self-sufficiency.

Bizarro world indeed. Keep praying, God seems to enjoy irony.

I believe Trump allowed the election to be stolen as to open our eyes in order to fix the holes on our election system. I don’t believe he thought he’d lose the fight though. I think he thought the evidence would be seen, heard etc but never counted on Mike Pence’s back stab not to mention fox news turning their backs or the courts not willing to do the right thing.

I also believe he chose swamp swimmers for positions in order to expose them to the world. and that has led to a real draining of the swamp.

” the people who call themselves “elites””. THANK YOU!

I am so sick of these arrogant fatcats, and calling them”elites”. They are as “elite” as Ebeneezer Scrooge, or that guy Lionel Barrymore played in “It’s a Wonderful Life”. They are mass murderers, engineering starvation, and they don’t think we see this?

This is intentional.

Hunger and starvation will put global mass migration into overdrive.

The UN is already handing out prepaid cards out (widely) to illegal aliens, paid for by US taxpayers.

They are the.largest single organised human trafficking cartel on earth.

The globalists have the key choke point in California. Newsome is a Schwab school protege, and election fraud decides that state every time.

yup.

yet another reason why I keep lamenting that eventually we will have to CONFRONT evil, not just run away from it. Its not enough to leave CA and let the fascists burn it down. At some point we will have to remove the fascists and restore the republic.

Don’t forget this:

https://thecounter.org/biden-administration-farmers-conservation-reserve-crp-usda-vilsack/

And then planting in winter for water safety purposes. Same climate change BS. Just a bit of bio-diversity here. lol

https://theconversation.com/bare-winter-fields-to-disappear-as-part-of-new-plan-for-healthy-greener-countryside-173190

First the planned demic and now the planned famine. Start paying attention when driving down the highway. Our best soil farmland being converted to solar farms. Why? There are hundreds of miles of poor soil and desert land available for such use not to mention a sea of roof tops. Permissive rezoning allowing housing subdivisions to forever replace productive farmland. Why? Why not prioritize revitalizing outdated residential areas already zoned urban instead of letting them decay? And then there are the miles and miles of once cultivated land being taken over by 5-10 years of scrub brush. Does that have anything to do with non-farmers like Gates and Soros buying up farmland?

In Germany 3 Nuclear Power Plant have just been shut down, in UK and France one plant each place, during a time with energy prices going through the roof!

It looks like we are first being bankrupt, and then reset (rescued) with a new government controlled amount of assets.

King John and the Sheriff of Nottingham won in the end?

I live in a rural blue state. Surprisingly, our local propaganda news station interviewed a long-time farmer who said exactly this. Shit is getting real. Real scary. How far with these insane despots go?

Did I hear word that bill gates bought up large swaths of farmland in the U.S.? What is that all about? Since I know often times “things” are connected, is there any nexus?

I wish I could take these ding bat “farm experts” and sit them down in a farmer’s coffee-shop 5am in the morning. They may actually learn something instead of mouthing off with total nonsense cockamamie.

In addition to the cost of fertilizer, diesel fuel which powers the equipment to plow, plant, irrigate (some pivots run on electric) , harvest crops and semi trucks to move it is a major factor as well. Also consider, depending on conditions, the price of natural gas used in grain dryers. How can we not expect the price of food to take a sharp increase? Availability of some agricultural based products will no doubt become an issue as well. Throw in unpredictable weather related issues such as drought, frost, disease and storms and it doesn’t take much imagination to envision a time when food prices affect a LOT of people.

Translation, global warming narrative is loosing steam but we still want more American money!

Try growing veggies on the streets in blue cities!

Sundance, we are at War.

No doubt, there will be interesting consequences when Chinese food dependencies are exacerbated.

Lesko Brandon!

Maybe all of us farmers should just take a year off and let our land be fallow until we teach the world a lesson in manufactured economic crises. We know how to feed ourselves and our neighbors. Why waste the last years diminished profits on people who have been stealing the agriculture industry blind for years.

I bet you guys really, really miss PRESIDENT TRUMP 😢

I DO!

What I’m planning to do for my community this spring into summer.

https://greencover.com/milpa/

That photo shop is perfect Sundance! I so want to kill these people! I’ve been a horticulturist for over 25 years, in all kinds of job sectors. There is not enough composted shit on the planet to fertilize plants for consumption. We are really seeing the shit hit the fan… Fertilizer and Glyphosate are essential for feeding the world. The well meaning hippy types in my field have no idea what their la la ideas of their la la world really look like. I’ve about blown their poor little minds with reality talk, I’ve felt sheepish when I see their crest-fallen faces. I have grown children and grandchildren that thankfully have an idea of what is ahead for us and the world.

I know from reading comments, that there are those here, who do not know the Lord Jesus Christ. I pray when they see their bones showing through their skin that they will repent and ask Jesus to save them. He is real and this is for real, famine is coming! Revelation Chapter 6. Sure we will fight to the end…

Come Lord Jesus! He is King, end of story.

Hollywood is so in our face with soft-disclousure in their Luciferian way. Hunger GAMES!

If they indeed want to reduce the planet’s population, what better way to do it?

A good follow-up to this story would be an investigation of farmland ownership by Bill Gates. Who else is buying up large tracts of farmland, and why?

Sundance, don’t miss the connection between fertilizer, the looming Russian-Ukraine war, and the Administration fools whose actions may be making the world stumble down that road, a la 1914, into WW3. Russia is the largest fertilizer exporter in the world, and the 4th largest fertilizer producer. If a tit-for-tat sanctions escalation happens between the West and Russia over Ukraine, or a war otherwise cuts off Russian fertilizer exports, the food security situation will escalate dramatically. Escalating energy prices are also reducing fertilizer availability and piling on to the same end. See, e.g., https://noqreport.com/2021/10/31/oh-crap-fertilizer-shortages-could-become-the-death-knell-for-global-food-production/.

So the spark that starts the revolution against the global elite cabal may not be in defense of our constitution, yet it may start where hunger is the driving force. The failure of a few two-bit dictators should get the ball rolling well.

Boston Tea Party Style….

If this draconian push keeps up and over time results in a critical shortage of food meant for human consumption a shift in production may eliminate feed for the dreaded livestock that the left hates because of it’s flatulent global warming causes and also pet food. JoeBama administration has three more years to push the agenda even if the feckless republicans win majorities.

There is a part of Sundance’s excellent economic summaries that needs to be read again. The part concerning MERGERS, Acquisitions and CONSOLIDATION of Ownership within Major Economic Sectors. There is a multiplier effect when looking at purposely executed assaults on Supply Chains and enacted Government Regulations (ALL Types-Green, Medical, Tax, et al related).

Fidelity Posted an most interesting graph on the education site last night, while discussing the impact of Consolidated Ownership within Sectors on Inflation. The focus was on the ownership and they only alluded to the multiplying impacts of Supply Chain Damage and Regulations. In a nutshell:

The graph showed the cumulative %Change IN CONSOLIDATION INCREASE-DECREASE since 2000. the interesting part was the slope of the line used to show the %changes.

2000-2009 Up on a slow rise during Bush II

2016-2020 UP on a very steep rise during Obama

2017-2019 FLAT during beginning of Trump Administration

2019 A curious spike that aligns with 2018 Elections

2019-2020 FLAT again

2021-2022 Beginning of New UP Surge at a steep slope JoeBama

Fidelity attributed a significant part of the rise in inflation to CONSOLIDATION and the corresponding attributes of partial monopolies that go with it. Now magnify or multiply the impact via Supply Chain destruction and Regulations-Mandates and the real looming disaster gets even more ominous.

By the way…There are now Bitcoin based IRA’s being offered via TV Commercials for those watching one Global Currency evolve.

Fertilizer can cause cancer! Organic has become a buzz word but in the old days that is all there was because manure was used to fertilize. We have become lazy and fat because we can stop for food at restaurants and not have to cook. A treat once in awhile, yes. We need to get back to baics. The crap they put in processed food is disgusting.

Don’t overlook the weather impact on vegetables grown in the south that are majority sold to food processors. Between the torrential downpours, tornadoes, drought, unseasonably cold fall and arctic blasts repeatedly hitting this region so far this winter. Already citrus crops are now downgraded and Calif crop yields are also expected to be low . 2020 NW summer flooding caused thousands of acres of seed potatoes to be ploughed under, 2021 drought continued to see potato shortages and the fall rains and unseasonably cold temps this winter will again challenge potato farmers. Few recall the 2021 spring/summer drought across North Dakota resulting in much smaller than usual wheat crops. All at the same time futures contracts bought by China will put 61+% of worldwide wheat in their silos, 57% of the world’s corn and 60% worldwide rice.

Simply stated, U.S. food supplies (both fresh and canned/processed/dehydrated dry pantry) will also present increased prices and scarcities. Couple that with supply chain logistics and America will be struggle for food like the rest of the world.

Only two years after I predicted it. Good for them catching up.

Food prices are UP because the cost to farmers to PRODUCE the food is up. WAY UP.

Compared to last year, the price of nitrogen based fertilizer has increased from about $500 /ton to $1250/ton (250%)

But, WHAT could cause such a drastic change?

Well, do ya think it has anything to do with the fact that 90% of the cost of PRODUCING that fertilizer is the Natural Gas used to produce it?

https://www.marketplace.org/2021/11/11/farmers-face-rising-fertilizer-prices-and-supply-constraints/

BIDEN’S war on fossil fuel is affecting a LOT MORE than our “At the Pump Gas Prices”