Many CTH readers know I have been involved in hurricane prep and recovery as a longtime member of a civilian emergency response team. I have physically been through four direct hurricane impacts and responded to recovery efforts in more than fifteen locations, often staying for days or weeks after the initial event.

Through the years I have advised readers on best practices for events before, during and after the storm. In this outline my goal is to take the experience from Hurricane Ian and overlay what worked and what doesn’t work from a perspective of the worst-case scenario.

Hurricane Ian was a worst-case scenario.

Let me be clear from the outset, I am not advising anyone to put greater weight on my opinion or ignore local emergency officials or professionals in/around the disaster areas. What I am going to provide below is my own experience after decades of this stuff, against the backdrop of Ian, and just provide information that you may wish to consider if you are ever faced with a similar situation.

Hurricane preparation can be overlaid against other types of disaster preparation, there are some commonalities. However, for the sake of those who live on/around the U.S. coastal areas where hurricanes have traditionally made impact, the specifics of preparation for this type of storm are more pertinent. I’m going to skip over the basic hurricane preparation and get into more obscure and granular details, actual stuff that matters, that many may not be familiar with.

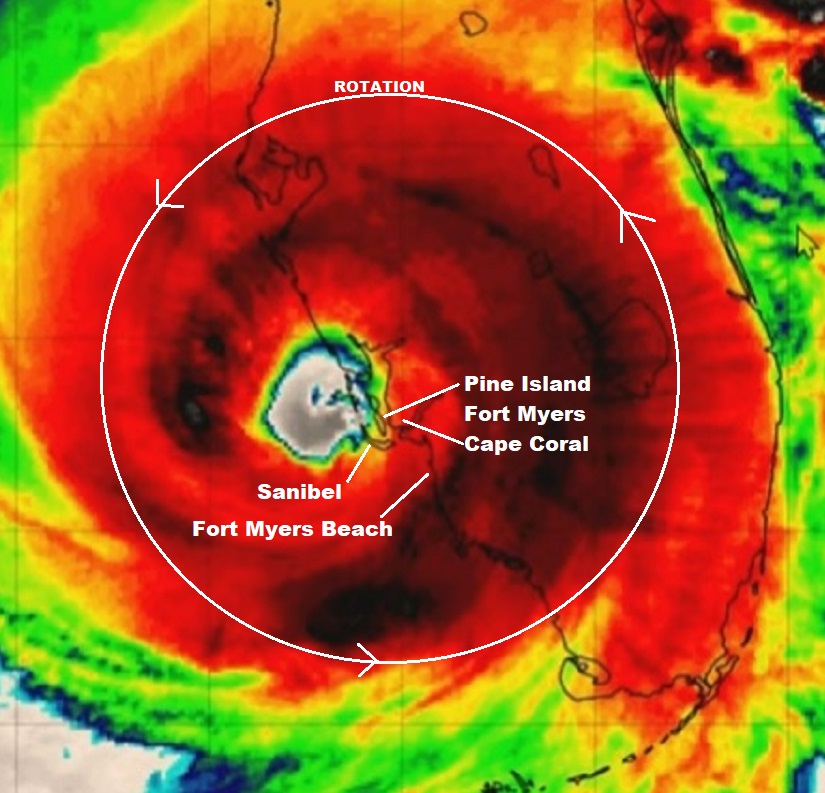

Let me start by sharing a graphic that you may overlay with the information you may have already seen from national media coverage. The graphic below shows Hurricane Ian in relation to Southwest Florida and points to locations that you may have seen on the news. The context of understanding Ian is going to be critical when contemplating preparation, so it must be emphasized.

This satellite image was likely taken around 4 to 7 pm on the evening of September 28, 2022, approximately three hours after Hurricane Ian officially made landfall at Bokeelia, a small community on the Northern end of Pine Island. All of my discussion below is from the ‘major impact zone’.

The satellite image above was taken during daylight after five or six hours of hurricane force winds (150+ mph) had already been impacting the SWFL coast.

For the areas of greatest impact, the event began roughly around 1:00pm and lasted until around 9:00pm. Ignore the red and dark area (rainfall) and instead focus on the green/blue ring around the eye, that is the “eye wall”, or what we call the “buzzsaw“.

From the perspective of the Fort Myers Beach, Cape Coral, Pine Island and Sanibel area, the first round of severe winds came from East to West around lunchtime on 9/28.

By 2pm the entire SWFL coastal region was without power. The easterly wind lasted about 2 hours, then as hurricane Ian meandered off the coast (retaining fuel) in a generally north-northeast direction, the winds shifted coming from the South. This is when the buzzsaw really started destroying buildings and infrastructure.

Ian was only moving in a forward direction around 5 to 8mph. That 150 mph buzzsaw (eyewall) is about 40 miles wide. Only half of the buzzsaw (the eastern side) was over land. The western side was providing hot water fuel the entire time. That buzzsaw was over the SWFL coastline for more than 8 hours.

Sanibel Lighthouse, Before and After

At approximately 5pm the most severe part of the storm surge started coming into the SWFL coast as the South and West winds began pushing massive amounts of water from the Gulf of Mexico onto the coast.

You have likely seen video from Fort Myers Beach as these moments were happening. The storm surge continued growing in scale for several hours. Combined with the wind, this storm surge is what erased most of the structures on Fort Myers Beach, Sanibel, Captiva, Upper Captiva Island, Saint James City, Pine Island, Matlacha and Bokeelia.

The 5 to 9pm timeframe is also when most of the flooding and storm surge damage took place in South Fort Myers and Cape Coral. Even after the buzzsaw cleared the area (9pm), the winds from the West at the bottom of the storm kept the water level high.

The water exit (back into the Gulf of Mexico) did not begin until the tidal shift after midnight. Due to the slow movement of the storm the total time of the storm surge impact was a jaw-dropping 8 to 10 hours. Many people drowned.

The old axiom remained mostly true, “hunker down from wind, but run from water.”

Now, I say “mostly true“, because to be brutally honest -due to the unique nature of Ian- if you are going to be inside that killer buzzsaw for 8 hours, hunkering down is really not a safe option. Fortunately, Ian was a rare system in terms of its slow-moving nature, even after hitting land. Most hurricane impact events are less than 3 hours in duration. Ian was dangerously unique.

To give scale to the size of the buzzsaw, again we are talking about the most dangerous part of any hurricane – the eyewall itself, this next image shows a comparison between the eyewall of Hurricane Charley in 2004 and the eyewall of Hurricane Ian in 2022.

That is the eye of Charley overlaid inside the eye of Ian in almost the same location. You can see how much bigger the buzzsaw was for Ian as opposed to Charley.

Both Hurricane Charley (’04) and Hurricane Ian (’22) came ashore in generally the same place. Charley made official landfall at Upper Captiva Island and Ian at Bokeelia. The distance between both landfall locations is only about 4 miles apart as the crow flies.

Both storms were Cat-4 landfall events. However, Charley was much smaller, had a smaller buzzsaw and moved quickly around 20 mph. Ian was big, had a much bigger buzzsaw and moved slowly around 5pmh.

The duration of Charley was around 2 to 3 hrs. The duration of Ian was around 8 to 9 hrs. Ian was bigger and just moved slower. Inside this distinction you discover why, despite their almost identical regional proximity, the damage from Ian was much more severe. Topography was changed.

I am focusing a lot of time on this similarity aspect because you cannot take a previous storm reference as a context for your ability to survive the next storm. They are all different, even when they hit the same place.

While more SWFL people evacuated for Hurricane Ian, and that is a profoundly good thing, the memory of getting through Hurricane Charley likely made many people think they could just prep, hunker down and get through it. The “I got this” reference of surviving through Charley may have led to people dying, because Ian wasn’t Charley…. not even close.

Having said that, I personally over prepare for these events. This time it was critical.

You have likely seen video from the hurricane area during the event. You have likely seen video from areas in/around the impact zone.

However, let me tell you something you have not seen…..

…. you have not seen any video of what was happening inside that eyewall. You have not seen any video of the buzzsaw at work.

Why? Because anyone who would attempt to step outside a structure into that buzzsaw would not survive. Any CCTV equipment, camera or video recording attached to a structure inside that coastal buzzsaw was almost certainly destroyed.

A physical human body does not step into 150 MPH winds and return.

This is a fury of nature, a battle where the odds are against you, that you may or may not be aware you are contemplating when you are choosing to stay or evacuate. It’s not the hurricane per se’, it’s that much smaller killer buzzsaw – the eyewall- that you are rolling the dice, never to see.

When it comes to the eyewall, the truest measure of the “cone of uncertainty“, the difference between scared out of your mind and almost certain death, is literally a matter of a few miles,…. and there ain’t no changing your mind once it starts.

Part II Here

😲

Excellent. Many weather men/woman should take the time to explain this. It would not be to scare everyone, but to teach the younger people who have never experienced the severe danger and threat of a hurricane. As well to inform people who may have moved to any of the coastal areas and have not experienced the noted danger. Thanks Sundance.

In Florida east central, Charlie blew by, very short duration. Ian was slow and rained like I’ve never seen in 30 years in Florida. Not comparing here with SWFL, I agree that many people will gauge risk by what they’ve seen or experienced before. Been there, done that doesn’t always apply. In Florida the local news always jump on any potential storm, it’s their biggest broadcast, so you tend to say here they go again, hyping the storm. Not in this case, they may have underplayed this one, at least initially.

Where Public policy comes into play, ….

After every major event like Ian, Katrina, etc. there are voices of sanity, that make their argument and are promptly dismissed.

Barrier islands exist for a reason; they take the brunt of these storms.

WHY are people living, and building homes and lives in such locations?

Govt authorises such behavior, by granting building permits.

And fine, someone who understands the risk, and accepts the risks, decides to build their home, or locate their business in a flood plain.

But WHY is the Govt subsidising FLOOD insurance.

The Insurance companies aren’t STUPID, they run the #’s, and refuse to ‘offer’ flood insurance in these areas, cause they know its a losing proposition.

And so, the Govt steps in, and offers “flood insurance”; so “development” can occur, in places that ‘should’ not be developed.

A few have, once again written op-eds, making this argument.

Once again, they will be IGNORED, everyone will focus on rebuilding on these barrier islands, some WILL leave, but others will move in to take their place, over time.

And ANOTHER Hurricane will come through, and start the merry-go-round, all over again.

You are spot on Dutchman in everything you have said.

.

In a strange way the buildings, structures and trees on barrier islands act as friction ( wind breaks ) for inland homes and businesses.

.

But should barrier island development be subsidized going forward? Places I love to visit but would not ride out even a tropical depression.

Amen

And the people who “vow to rebuild” are often seen as “heroes” for their “never say die” and “can do” spirit”. Insane!

Yep, absolutely correct. And as we are folks who pay for flood insurance OUTSIDE of a flood “way”, it’s beyond ridiculous that re-building is permitted. It is a GIVEN that a hurricane will strike again, just as it is a GIVEN that a major river will flood with the right circumstances and rainfall.

The homeowner should bear the burden of the the coverage…if you want to continue to live in a danger zone, you need to foot the bill.

Can’t count the number of times the fire company and police have come by to warn us of impending disaster…we choose to stay in a flood situation. Would NEVER stay in a hurricane…just too unpredictable.

The legislature passed The Growth Management Act in 1985 to plan for appropriate land use and development conditioned upon development of infrastructure, including water, sewer, parks, roads, runoff, evacuation resources, etc. Jeb nuked the state DCA Department of Community Affairs which reviewed the city, county growth plans for consistency. Local governments caved to developers since they make the large campaign donations.

https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/IR/00/00/13/52/00001/FE64300.pdf

Jeb! strikes again. We dodged a bullet when Jeb! lost his bid for the POTUS nomination.

Bingo. What a joke that guy is.

Jeb!

I refer to him as Jebra.

(Think Debra)

Developers will build on anything to any density without regard for whether the infrastructure of the area will support it. They never consider roads, water, sewage, electricity expansion. So, cities end up paying and people end up dealing with life in areas where there are too many people for life’s necessities. It was done in San Diego far inland. So, developers should have constraints based on the geography of where they are building, but, they do not.

It seems too many people have ignored the parable Jesus told nearly two thousand years ago of the man who built his house on the sand. He told this parable because the people of his day clearly understood the risk and foolishness of this man.

This is NOT the meaning of that parable. False teaching. Shameful. Will call out anyone falsely teaching God’s Word TO FIT into their little story. Tell the story without falsely using God’s Word to prop up your story. Shameful.

No, it s not the meaning Jesus intended to communicate, but it is precisely why He used that metaphor / parable to illustrate His message: faith built on false teachings is not going to sustain the person.

Hs parable (illustration) was effective because everyone (at least back then) knew – houses built on sand are unstable and often don’t last very long. I’m pretty sure they did not all understand the spiritual meaning.

He’s misapplied the parable. It’s a spiritual truth – NOT something to berate people for building on barrier islands.

Using a parable out of context to support one’s point of view is the misuse of spiritual teachings/truths.

The parable is a spiritual truth ob basing one’s faith on Jesus Christ as the Messiah and Savior, and to put one’s faith in any other person or item will wash away like a house with a bad foundation.

Using this parable and spiritual truth to justify the concept of one not building on a barrier island is false teaching, which has nothing to do with the spiritual doctrine.

When one uses spiritual trust to correlate to a scenario today THAT is the proper and ONLY use of spiritual doctrine. You do not take the spiritual message out of the doctrine and THEN say it’s okay, fine, to leave God’s Word behind as long as it suits one using it to support one’s argument.

Had Honesty left all the references to the Bible, Christ, and the parable OUT OF his comment and just included the house being built on a bad foundation, that would have been fine. Otherwise, it’s false teaching.

Compromising God’s Word is always false teaching. It’s why the Church is in a mess today, as are many Christians.

Read the last warning given in Revelation 22. Says it all.

If you disagree, then name the SPIRITUAL DOCTRINE in the comment.

MaineCoon, I think my previous reply clearly indicated that I disagreed with applying that parable to criticize building on barrier islands. But I maintain that the bios example used by Jesus was based on a true principle that was understood even by people who weren’t mature enough in their zoe life to understand the real lesson of His parable.

That’s my only observation here. I don’t believe we need to debate the spiritual/ doctrinal aspect of the parable in this discussion – you and I agree on that.

The pyramids have stood fairly well.

True. And one of the arguments for rebuilding will be that “Ian was a hundred-year storm”, so go ahead and rebuild on that little strip of sand, you will die of old age before Ian Number Two hits.

Do I agree with that line of reasoning? Nope, no more than I’d seek a building permit for a lot near the base of Kilauea. Only the Lord knows when the next hundred-year storm will hit … and to the Lord, one day is as a thousand years … in other words, His clock and mine do not always agree.

I work as a civil engineer specializing in floodplain and other hydraulic modeling.

For its many faults, FEMA has starting doing one thing better…

They are moving away from terms like “hundred-year storm”, using terms like “1% storm” instead. They are doing if for the very reason you brought up. Too many people think that because they just had a hundred-year storm, another won’t occur for another 99 years.

Do I think it will help? Not really. I’ve found that — in general — people have a very poor understanding of statistics and this sort of risk management.

That’s great to hear!

When I first started working out of college I did a lot of storm water work.

The concept of the 10, 25, 50, and 100 year storms was difficult for me to grasp.

The person I was working for explained it much better than my professors did.

The probability concept still was difficult for me to grasp. Eventually, I caught on. I enjoyed doing that kind of design work.

We would joke about designing for the 25 year storm that happened every 10 years.

Amen!

Trump’s golf course in northern Va. suffered two hundred year floods in back to back years. This was just after it had been constructed alongside the Potomac river. He didn’t own it then.

So it happens.

If you look at Ocean City MD, and follow the barrier island south, you will find the remnants of a town called Ocean Beach.

In the 1950s, developers were going down the coast, extending the urban beachfront from Rehoboth, Bethany, Fenwick, Ocean City and the next new to be developed area, Ocean Beach. It was going to end up like Ocean City NJ, a sprawl of houses, hotels, and rentals. They had laid roads and utilities, set up a firehouse, and were actively selling to anyone who wanted beachfront (mostly NYers). Almost 6000 plots were already sold, and construction was underway. At least until 1962, when a nor’easter, the Ash Wednesday storm, wiped the development near flat. It parked off the coast for five days, with storm surge measured at 40 ft in Rohoboth DE. Cars were buried in 5ft of sand. Damage was in the multi-millions.

The developer declared bankruptcy, and the land was taken over by the state 3 years later forming the Assateague Island State and National Parks. They felt that the land would never be safe, and it was only a matter of time before everything was wiped clean again. It is perhaps the only oceanfront campsites today remaining on the east coast, with wild horses, nature preserves and no urban development.

It’s beautiful.

I was 4 that year and we lived in Lewes DE, on the Delaware Bay 7 miles northeast of Rehoboth.

My parents talked about that storm for years.

FEMA is a nationwide government program. I lived in a condo in WA state next to a river. Because it was in a 100 year flood plain and had a amall mortgage I was required to carry their flood insurance. What I learned is if there’s a hurricane in Florida FEMA will raise the rates in Washington state and on everyone in the United States, to take up the slack. So everyone with FEMA insurance is paying for hurricanes everywhere. Being on a fixed income I decided that this was not wise.

I decided I did not want to live in a flood plain anymore so I sold and moved to FL, not in a flood plain and no mortgage.

All homeowners insurance in Florida was already getting unaffordable. In my opinion there will be no insurance companies left except the state run insurance company which is called Citizens and I don’t believe they cover water damage. But everyone in at least the State of Florida is going to pay dearly for homeowners or find it so unaffordable that Florida will see a mass exodus.

Only politicians can solve this and they won’t be in session until next March.

You understand Florida has been there longer than you, that is is still standing, and it is GAINING people. There will be no “mass exodus”.

It’s a hurricane, a particularly nasty one. There will be more. And mankind will withstand them and prosper.

We just bought two houses in NC/NE Fl, 2019 and 2021. They were both in the path of Ian..my thought was oh well..if they get hit we had a good time while it lasted..my parents house burnt down twice, first time it was hit by lightning on Halloween Day, 1989. Lightning strikes are quite common in the area. The second time was 20 years later, my mother was killed. Dad lost everything..we rebuilt six years later.

That has nothing to do with the cost of homeowners insurance, which was his point.

I know people who only carry liability because they just can’t even get homeowners insurance in central Florida, which is not at risk from storm surges and much of it is not at risk of flooding.

Citizens is often referred to as “Insurance of last resort”. Our Ins. Commissioner here in La. just gave them permission to raise their rates by 60%. Horrendous. Would hate to be on that hamster wheel.

“The Insurance companies aren’t STUPID, they run the #’s, and refuse to ‘offer’ flood insurance in these areas, cause they know its a losing proposition.”

This is not true. The insurance companies cannot compete with subsidized insurance where it is offered/forced upon the homeowner.

I have a home on a barrier island. The Atlantic is <150yards from my home. I have private flood insurance because a coupe years back the new flood map said we were good. Private flood insurance, on a barrier island, within sight of the water. And it’s my cheapest insurance because I have normal homeowners, the wind and hail. The flood is well under $1500.

Let us know when your insurance renews what the percentage of increase is. Many people in this current depression will not be able to afford their renewals.

My insurance just renewed since I originally purchased the house in October. Rates on the homeowners increased the most, wind and hail policy a minor amount. Flood remained almost the same.

Our property insurance rates doubled last year and are scheduled to go up 40 to 60% in February. Based on pre-Ian information. Rates won’t be available until January. Surfside collapse had a big impact. I live in a large condominium complex, no building that’s over two stories. Everyone’s HOA will have to increase.

Many fixed income folks and Joe’s inflation will be untenable for many who moved here when low cost of living was prevalent. I am on the insurance committee and have interviewed top insurance brokers about Florida’s situation in this regard.

We had our Florida State Rep to a meeting a couple of weeks ago. There was a special session in Tallahassee to address the impact of the Surfside collapse. She said the Insurance Commissioners bureaucrats were unable to produce the necessary reports for the legislature to pass good legislation to address the problem. She said an insurance company, to enter Florida only has to have $15 million in reserves to enter the State, which is ridiculous. 15 companies have left the State this year, which is making Citizens more likely to be one of the last options for people, since it is the company of last resort. Citizens is government insurance, so government will have to hire many new people to cope with the increase in properties insured. Taxpayers will have to fund Citizens reserves. Citizens will have to raise their rates accordingly.. This is making for an added expense many people who moved here in the last couple of years could not foresee.

And to top it all off, you have to replace your roof every 10 years or lose your insurance.

That’s right. And no solar panels. The nightmare is going to get worse. So even if the insurance companies I have the funds to rebuild SWFL and beyond, a crisis will follow because no one but Citizens may be here to insure us. A government entity, just what we’re trying to avoid.

Not if you have a metal roof.

Go away.

Government ridiculously underpriced flood insurance for decades with the real estate industry pressuring ($$$$$$$) Congress. Now it’s more fairly priced and expensive. hence many people chose not to buy it to their peril.

Note to self, get multiple Internet carriers to house before large mega storm.

Quantum Fiber – CenturyLink guys say they can’t get parts, supply chain delay issues.

.

Quantum Fiber – CenturyLink publicity folks say Cape Coral might have to wait till February for restoration,

Even before Ian underground cable & including fiber optics was getting scarce. My husband works for an underground utilities company and they were getting worried about where it would be coming from. He said it has to be paid for upfront now which is a big change.

Nobody keeps inventory anymore. Especially for “just in case” situations.

I’ve seen utilities scramble for poles, cable, and transformers after a line of nasty summer storms blows through. Often looking out of state for those things. Then moving heaven and earth to get them.

Repair foremen and supervisors would keep stashes of cable to splice around trouble if needed. They would go to great lengths to hide them from the back office bean counters.

The cutting and gutting always got worse of there was a merger afoot.

Thank Brandon’s superb economic planners for the supply chain issues.

They just decapitated China’s semiconductor industry by telling the Americans working in country to choose between their employment or their citizenship.

This will not only massively exacerbate supply chain issues, it gives China an existential rationale to size Taiwan.

As Joke Biden is wholly owned by China, I suspect this war justification was a well coordinated gift.

Thank you for explaining and teaching Sundance. I live in AZ and might never have anything like this but I see the importance. The pictures of the Lighthouse on Sanibel Island tell a story.

Thank you Sundance for telling us the story we will not get anywhere else. Also,THANK you for what you do for your community.

Apply the lessons for your climate.

Arizona is a desert – focus on water, food and cooling (yourself and perishable food) if power is out for an extended period, for example.

Indeed. The MalAdministration threatens all our lives via disruption of all we need, nationwide.

I don’t know of a place that isn’t subject to weather events, of some type.

It rained here in North Texas all day yesterday…bless-ed rain we have not had for weeks and weeks.

Halfway through the day, suddenly from nowhere, came the most ferocious, intense winds which ripped leaves from the trees. For about an hour…a single hour…the sounds of this unrelenting wind was unnerving. Then as suddenly as it arrived it was gone. We hoped our roof survived.

Reading your description, Sundance, put into terrifying context what Ian’s brutal, destructive, sustained onslaught was like. Hour after excruciating, terrifying hour. Not knowing for how long it would go on, or what would be left (if anything) when it finally passed.

I have a vivid imagination, but not even with that can I comprehend just how it must have seemed as if the end of the world was at hand. I know lives were lost. A tragedy no matter how it happens. But that so many more weren’t??

Deo gratias🙏

I’ve been through some startling “Blue Northerns” in the DFW area, they are a great reminder of the Lord’s mighty power.

.

But this ol’ storm IAN in SW Florida was a life perspective changer, almost annoying in its persistence.

.

I personally felt moved of the Lord to rebuke the wind gusts about seven times during IAN!!!

.

A little like the film clip blow, only I did not stand outside. ( That would have been nearly suicidal. )

.

Thanks for that link, Bob. You are right. I always think of winds as the breath of God. Not sure how to interpret the winds from Ian…

Great analysis Sundance!

Have you given thought to more inland areas in FL? We moved north and east by 10 miles. It was nice to not HAVE to evacuate, but even where we are we would have left with Ian. With the size of that storm there really wasn’t a good direction to run from the Tampa bay area. We stayed and got nothing but a little rain. Been lucky for 50 years, sure going to get ours before we leave this marble.

Yes, that is an important part of the decision making, both size of the storm and it’s projected intensity.

When I lived on a barrier island, I always evacuated. But, now, I am just far enough I can stay put depending on the size and intensity of the storm. I would have evacuated for Ian if I had been in the cone of its initial landfall whether I was on a barrier island or 10 miles inland.

well said – excellent advice – thank-you

The hurricane just stopped off shore, and kept on spinning around and around for several hours without moving. The live coverage YouTube weather dudes and their storm chasing teams on the ground had never seen anything like it before.

Its the weather, gov is playing with it. They couldn’t let it hit Tampa too many people so that is why Charly and Ian took a hard right into the coast. I heard that one yesterday at Walmart. Well they seem to be planning to starve us so say the conspiracy theorists./s

First rule, don’t build on vulnerable islands or coastlines. Second rule, if you CHOOSE to violate the first rule evacuate when any storm approaches.

Projectiles alone just gives one thoughts

to ponder on…. Remembering the piece

of shingle slizing into your radiator you

mentioned Sundance.

His Blessings and Strength

When I was 12 or so went through a Easter outbreak of tornadoes and it hit a lumbar yard and for miles there were 2×4’s through trees everywhere. Yeah the wind is wicked.

Damn! This gave me goose bumps just reading it.

It is not like one knows exactly where the “buzz saw” will hit since hurricanes wobble and Ian was no exception.

I still doubt that Ian has sustained 150m mph winds. I figure it was about 8- 10 mph less than that. That is neither here nor there though because the real story of Ian was not the windspeeds but the storm surge and flooding and considering the massive surge it produced the deaths were actually pretty low.

The slow movement that resulted in the surge and flooding being so severe also has a negative effect on windspeed because there is more time the leading edge feeder bands of the storm are over land before the eyewall makes landfall. The bigger the storm the more that is a factor and Ian was a medium to medium large sized hurricane.

The Saffir-Simpson scale needs to be replaced by an impact based measuring system. It served its purpose at the time but now we have the technology to make better judgment and forecasts of a storms true potential and likely hood of the mode of destruction than just graduated windspeed scale. Storm size is a critical factor in producing surge. The larger the storm the larger the area of raised water under it due to the low atmospheric pressure and the longer the winds will be pushing the water on shore.

HARP is being used for most strange acting storms.

The windspeed reported are not actually measured directly. They can’t be since the criteria for the Saffir-Simpson scale wind speeds is 1 minute sustained as measured by an unmasked station 10 meters above the surface. IOW under those criteria only surface stations have the ability to directly measure windspeeds. It should be noted that buoy data is valuable but generally not reliable for real accuracy as far as measuring windspeed per the Saffir- Simpson because of wave action.

The dropsondes from the hurricane hunters obviously can’t hover at 10 meters above the surface for a minute even if they could stay positioned in the eyewall.

So what we get is a combination of various remote sensing data and the pressures the dropsondes measure put through a formula to estimate what the windspeeds at the eyewall are based on their calculations and not direct measurements of actual windspeeds. That is all they have until a land station meeting the criteria for Saphir-Simpson survives to take a direct measurement of the wind in the eyewall.

The windspeed in a storm varies considerably based on the altitude it is measured at. Windspeeds taken closer to the surface will be slower because of friction with the surface. Windspeeds taken at say 500 feet above the surface will be considerably higher.

Hurricane Alicia in 83. The eye went just to the east of us down near the bay. Boats lifted up and moved like a child throwing legos across the room. Massive live oaks toppled like the scene from Two Towers (Lord of the Rings). We hunkered down and it was like a Locomotive running through the house all night. The eye passed through in the morning. Everything was leaning 30 – 45 degrees in one direction…..then the eye passed and we had to spend the rest of the day inside until the winds died down. Our leaning trees almost uprighted themselves with the opposite winds after the eye passed. This started after dark and lasted until the next afternoon. The devastation was significant. This storm was a deadly wind event with a big storm surge ( think cat 4 when it hit Galveston and 3 when it hit us (Galveston Bay near Kemah).

Ike was a water event that flooded everything in that same area. I was fortunate to be in England at the time and watched the devastation on TV. For Harvey we hunkered down for and it was a massive downpour all night long. I think 30 inches in just a few hours. My house was fortunately on the high spot and we had no outages nor flooding inside the house.

I used to contract in IT with FPL doing Work Management Field Automation Software, and spent I think 3 Hurricanes (including Charlie) with them 2004-2005 supporting our software in make shift hotels with the linesmen to help them with our application. We got to see a lot of things out on the road which gives a broad sense of reality and other’s experiences.

So sharing your experience is appreciated. I will never stay again. Seeing the devastation that mother nature can bring, respect is a better choice. I’ll just board up and take a vacation somewhere else.

Also, my wife and I vacationed in Pine island for a week @2004-2005. Beautiful place, was sad to see the destruction.

.

Before the first time I ever heard the sound that this kind of wind makes, I could not imagine it.

.

I took a direct hit from Wilma in 2005. Wilma was for the most part later downgraded to category 1 in most places. I was directly on the strong side eyewall, and ended up with about 6 hours of winds probably 115 miles per hour. Good solid Category 3 stuff. 5 miles north or south the damage was considerably less. My farm was destroyed, and a nearby trailer park was completely wiped out. Charley the year before was the freak of freaks. For years after that storm you could drive north on I-75 and there was a clear cut line of destruction much more like an EF 5 tornado. Literally south side of the line was fine, north side of the line was destroyed. So yeah that buzzsaw matters a ton.

The most amazing piece of hurricane video I’ve ever seen. It’s only four or five minutes long. Watch Charley destroy a gas station in under 2 minutes.

The bullet Florida dodged was Irma in 2017. For the better part of a week, it was forecast to go straight up the peninsula as a category 5. It hit Big Pine Key full strength, and somehow moderated considerably before it hit Naples. We dodged a major major destructive event.

I’ve an idiotic urge to get out and drive in big weather events, but this video is close enough to real hazard for me; I’ll stay here in the Inland Pacific Northwest, thank you very much!

I remember this if it was the service station by the bridge over into Punta Gorda. DH and I were in our home in Lake Suzy, no shutters. Most people didn’t have shutters as there hadn’t been a hurricane in the area for 40 years. Did you notice gas was $1.88/gallon?

.

“Relatively weak” Wilma hit us directly as a Cat 1. It sounded like a train roaring. Debris smacked the house, and on the hurricane shutters was a constant bang bang bang.

You could preiodically hear something more — the sound of “gusts”. During one, there was a loud cracking sound that we later discovered was the entire screen over the pool being picked up, torn from the house, and thrown into the lake 40 feet from the house.

Then another bam on the other side of the house — when the quiet came when the eye went over, we discovered an entire orange tree uprooted and laying on the roof. The winds going in the other direction later picked up that tree from the roof, turned it around completely and re-set the thing down on the roof. Meanwhile, huge branches from an old slash pine on the other side of the house — branches that that had always looked small, being a hundred feet in the air, had broken off and not only littered the yard but completely filled the pool. Every shrub and bush in the yard, though, had completely “disappeared”.

We were fortunate, but a number of the neighbors’ houses completely lost all or part of their roofs. But then there was weeks of no electricity. I cannot fathom being right in something stronger than a Cat 1.

.

Wilma was a bad girl. The backside of Wilma was stronger than the front side, which makes no sense. I had set up a generator in the bed of my truck, and ran the cords into my house, and right when it started to get a little bit nasty ran out there and started it up. So I was able to watch TV and the progress of the storm throughout the entire hurricane. At a certain point I was pretty sure the worst of it was over. Boy was I wrong.

I will share this with Florida friends that think they are invincible. Thank you for a well written accounting of a serious and scary event, Sundance.

Agree. Doing the same, the piece is frank and absolutely worth sharing for both new and longer term residents in FL/LA/MS/TX… even GA/SC

I’m close the “P” in Pine Island on the first image.

One specific thing was notable, relative to Irma and some other ‘cains I’ve been through over on the “other side”, and it was this….

The wind surged a lot during the peak winds in the eye wall. That is, very large rapid surges, maybe every 20 or so seconds, in the wall winds without much rain banding. It was basically pulsing. That is what rocks the structures. 6 in Oak trees limbs, especially, were oscillating almost 180 degrees from the south to north direction in the vegetative wind break behind me. Try that with a rope and a tractor.

So, it also “sounded” different than the others.

Even so, there is one area about 3 miles from me that the county collects the vegetation debris after the ‘cains and basically grinds it into mulch. It is about 1/3 as full this time, as compared to Irma.

And, I’ve mentioned here before that I saw shingles blown off roofs in Belle Glades. That’s some pretty large stretch, folks, on the other side and bottom of Lake O.

Hah! “try that with a tractor and rope” and the “pulsing” you describe.

If you ARE going to try to move something big and heavy, anyone eho has done it knows, if a steady pull doesn’t work, you pulse or rock it.

So, that pulsing action you describe, was worse for the buildings etc. than if it had been a steady, unrelenting wind.

“Buzz saw” indeed!

Yup. And after you rock it from one direction, do it from the opposite one, just like getting hit by the eye wall coming and going.

Oaks thicker than six inches oscillating to and fro as you describe, exactly what we were seeing here on Manasota Key as well.

From 2PM until about 11PM, wife and I were in the third storey cupola, playing tug of war with west facing French doors. The bottom peg which holds the door shut worked itself up and out of the slot, allowing the pulsing winds which you describe to pull it a few inches from the frame, despite being bolted at the top and both the lock and deadbolt being securely shot.

We roped the door handles to the counterpart door on the east, and as well to the banister downstairs but still the winds would yank it every thirty seconds or so.

Winds were fierce from the northeast, blowing out forty percent of the soffits, tearing flashing from the roof and bashing it against the Kevlar which protected the windows many times over. Roof held on this traditional Key West style home.

Most fortunate. Many trees down, most every home has a ‘blue roof’.

Manasota Key is filled with all manner of storm debris from downed trees to flashing, soffits, lumber and home interior appointments, mattresses, appliances, you name it. Trailer parks demolished here. Northport is still a mess with flooding.

Our ‘gold plated’ Frontier landline worked throughout while cellphones were unreliable at best. DSL internet may be slow but again, it worked throughout while fibre-optic hi-speed Net is still down in Englewood area. There’s a lot to be said for copper wire telecomms.

Stored plenty water and food prior to the storm, and cash is absolutely king. You can count on internet failures long after power is restored, meaning cards can’t be verified. Don’t be without cash, lots of it. So much for the digital currency crowd.

Radios are invaluable both AM/FM and the two-way variety for communications. Batteries are a must along with those little LED lanterns for night use. Solar yard lights also work well indoors.

Generators can be tempermental based on fuel type and age but absolutely essential.

Living in a high state of readiness regardless of hurricane warnings means a lot less prep work is required. Any extra generator gas can be poured into the cars. A chainsaw is also a useful tool to have at the ready, along with lots of rope, shovels, rakes, etc.

We have long stored rope in the cupola. When one lives between Gulf and bay, it’s akin to living on a boat. Having rope topside literally saved our home by allowing us to rope the door shut and pull it tight. Had it blown open, it surely would have been torn off in the high winds which would have wreaked havoc on the home.

The sound of the fifteen to twenty five inches of rains blasting thru the Kevlar shutters against the cupola windows was akin to the sound of a two and one half inch fireman’s booster hose smashing against glass windows at a fire. Water was pressed thru the spaces between window and frame into the house. Having plenty of towels and buckets is a must.

Storms are much easier to survive when prepared.

Don’t forget that they kept changing the predicted landfall.

Tough to make the right decision based on the wrong information.

That’s why if you’re in the core on “uncertainty” anywhere on the FL peninsula you’d best be leaving. The FL Panhandle you have 3 directions to choose an evacuation route. Not so for the rest of the state.

You’ll be wanting to be out before all the EVs “brick” up the roads.

I have a feeling that if EVs brick up a road, others will take them out.

They’ll have to, but a car weighing twice normal with wheels that can’t even freewheel is difficult to move.

That’s why they call them bricks, they’re useless and heavy.

And, if they can’t accurately predict hurricane landfall, if they can’t make accurate short term predictions for weather, how much hubris does it take for them to believe they can predict long term changes?

As much as does their real goal of controlling the thoughts and actions of all humanity.

The long term weather predictions (warming, cooling) are now and always have been political ideology. That is why they keep changing. They have gotten much better at predicting hurricane paths since the 1950s/1960s. Back then they were still mostly guessing at the path. They ALWAYS missed a hurricane standing still or looping back onto land or criss crossing the state in the old days. Now, 80% of the time the hurricane lands in the cone. They have good numbers on the size of the hurricane, but, intensity is still out of reach. Several jump higher 24 hours before landing.

I’ve been through a derecho, the tail end of several hurricanes and Hurricane Irene in Maryland. We never evacuated and never got structural damage. I’m 20 miles from the SC coast now and appreciate this explanation so I can use it when making decisions in the future. Thank you.

Thank you Sundance for your update/article. I think in light of many FL newcomers it’s really an important piece.

Commendations to Sundance and crew.

I am sure I am not the only one who expected it to take a lot longer, for CTH to get “back up” after Ian.

WAY TO GO, and much thanks!

CTH going gray was an Ian impact felt ’round the globe.

One more thing, and I am still really P*SSED off at this…During Irma they were broadcasting on radio the DOPPLER WIND SPEED COMING TO SPECIFIC AREAS/TOWNS. In real time. They literally warned specific areas. This time it was all rain bands. Nobody cares about the damn rain bands–it’s a friggin’ hurricane. It’s the measurement of WIND SPEED IN THE BAND. NONE of the SWFL broadcasters presented it this time around.

Don’t ask me why. I still have no clue. But, 5 years ago all of their radar graphics could measure speed and rain intensity.

NOAA weather planes cloud seeding, HAARP and Dane Wigginton identified manipulation related to Ian:

https://rumble.com/v1m6jzy-controlling-hurricane-ian-by-dane-wigington.html

This is why weather events as entertainment is so dangerous. Even walking a beach during a tropical storm a person can be killed. And have been.

My father lived in PGI and the back of his house faced Charley’s path. The other houses on the street had their side walls facing Charley’s path. Charley ripped the metal and concrete lanai roof off and that roof severed a telephone poll across the street. The lanai roof also took the kitchen roof with it. Every window and sliding glass door and window was blown out and the double front door was blown out. The amount of damage was incredible with no appreciable storm surge.

I knew this storm was going to elicit some of your best writing.

Received with much appreciation.

I posted when Ian was south of Cuba moving North that Historical hurricane records for the last week in September thru October 10th had hurricane tracks moving over Florida along a line from Naples to Ft Pierce. Modern Computer models ignored history and the Science of why this is a common track at this time. Hurricanes moving North along the weak Bermuda High western edge have their wind hit the Florida Peninsula and wind goes slower over land than water( Friction) This slowing of wind over land causes a lower pressure pattern on eastern side and the storm moves into the low slot over land and continues this until the wind on the East side of the storm again speeds up as it once again feeds into the storm moving over water on the Atlantic side. The low pocket is removed and the storm begins it’s North movement once again along the Atlantic coast until it is captured by a cold front. Historical hurricane movement records for Florida forecasting have to be looked at and humans must not just depend upon modern computer programs. Ignoring the past science seems to be ok in this new world when scientist can no longer think out loud for fear of going against the computer solutions.

I think this is a strawman. If you followed the discussion on tropical tidbits and storm2k you could see how the GFS and Euro ensembles were predicting after Ian passed Jamaica and it was pointed out how the models were showing differences in the upper and mid level steering troughs in the forecast futures. Also some differences in how drier air was being pulled in from the west.

I agree. Tropical tidbits discussed the dry air coming at length. Quite informative.

I better understand what those (including SD) went through and the danger of such high winds.

Thank you for that info. It explains the utter devastation. You need a super morale to stick with the cleanup operation. You have my greatest respect.

Exceptionally valuable column. My son lives in Hobe Sound…moving down there 5 years ago. He doesn’t take these events with the seriousness that he should. This information was more than eye-opening for myself and will be passed along to a couple family members who live down there, as well as my son. My deepest regards, I am very grateful for this. Thank you!!

I live about 20 miles west of Port Charlotte that was torn up by Charley. I remember to the minute when my home felt Charley and the fear.

It was at 4 PM on Friday, Aug 13, 2004 and lasted for about a minute. The wind I feared may have approached 60 mph for that minute.

After Ian (I was out of state for Irma) I realized that being in a well built home with precautions taken like boarding up, once the initial minute of storm arrival had passed, my fear subsided and I transitioned into a “what if” state of mind and occupied myself with packing and preparing should the worst occur.

That second state was less mentally taxing because it prepared me to accept and deal with the worst to survive.

When Charley occurred I never reached that second state of mind.

While I will be occupied in recovering for some time and dealing with related issues, I believe I am far better off psychologically from the experience.

I have never been in a hurricane, but from this description, I imagine being in a space station in outer space where to leave your safe structure will evaporate you, or being stuck too late on the descent on Mount Everest, where no one can rescue you.

In a hurricane, the full force of nature whirls outside and you only hope your structure holds and the water does not reach you, as it comes under your door.

Terrifying and attention grabbing.

That’s why the person suggesting a life jacket is laughable. You only need that if you are in your attic with an axe hacking your way to the roof to stay above water. That happened in Katrina because of New Orleans topography. It happened in Houston because of surge and improper drainage. Your best survival strategy is to stay within four thick solid cement walls. If you have to get out through your roof, staying was a huge mistake. That is what Sundance means when he says RUN from water, hunker down from wind. If you are in a single story building facing a twenty foot storm surge, you should evacuate.

Always be prepared to hunker down and in this case be ready to evacuate. Stay in prayer.

I begged my friend to leave Pine Island the afternoon before it hit..she said they couldn’t get out. She posted a beautiful picture of her living room with all her artwork and the things she loved..I knew it was the last picture..She survived but lost everything.

Did Ian flood out the tunnels at Disney World?

I live on Pine Island on the Bokeelia end of the island. Many have seen my 100 year old fishing cottage built on an Indian mound. I stayed through the entire storm and do have video shot out a protected window of the buzz saw. First and last hurricane I will stay through; scratched off bucket list!

Wow. Have you uploaded it anywhere? I would love to see it.

Glad you are okay. You have an angel on your shoulder.

Sundance

I’ll post links tomorrow. Angel? Perhaps, but I did have a chihuahua in my hand and a glass of bourbon by my side!

BTW, got to do a shout out to the World Central Kitchen. They’ve served over 1,000,000 hot, gourmet meals in SWFL since Ian. Incredible, efficient bunch of folks who have really made a difference.