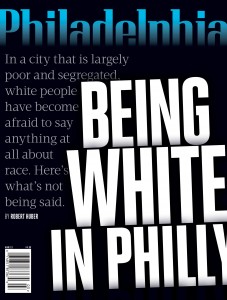

What it’s like to live in the land of the perpetually aggrieved

[excerpt from PhillyMag.com] I’ve shared my view of North Broad Street with people—white friends and colleagues—who see something else there: New buildings. Progress. Gentrification. They’re sunny about the area around Temple. I think they’re blind, that they’ve stopped looking. Indeed, I’ve begun to think that most white people stopped looking around at large segments of our city, at our poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods, a long time ago. One of the reasons, plainly put, is queasiness over race. Many of those neighborhoods are predominantly African-American. And if you’re white, you don’t merely avoid them—you do your best to erase them from your thoughts.

[excerpt from PhillyMag.com] I’ve shared my view of North Broad Street with people—white friends and colleagues—who see something else there: New buildings. Progress. Gentrification. They’re sunny about the area around Temple. I think they’re blind, that they’ve stopped looking. Indeed, I’ve begun to think that most white people stopped looking around at large segments of our city, at our poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods, a long time ago. One of the reasons, plainly put, is queasiness over race. Many of those neighborhoods are predominantly African-American. And if you’re white, you don’t merely avoid them—you do your best to erase them from your thoughts.

At the same time, white Philadelphians think a great deal about race. Begin to talk to people, and it’s clear it’s a dominant motif in and around our city. Everyone seems to have a story, often an uncomfortable story, about how white and black people relate.

Take a young woman I’ll call Susan, whom I met recently. She lost her BlackBerry in a biology lab at Villanova and Facebooked all the class members she could find, “wondering if you happened to pick it up or know who did.” No one had it. There was one black student in the class, whom I’ll call Carol, who responded: “Why would I just happen to pick up a BlackBerry and if this is a personal message I’m offended!”

Susan assured her that she had Facebooked the whole class. Carol wrote: “Next time be careful what type of messages you send around and what you say in them.”

After that, when their paths crossed at school, Carol would avoid eye contact with Susan, wordless. What did I do? Susan wondered. The only explanation she could think of was Vanilla-nova—the old joke about the school’s distinct lack of color, its perceived lack of welcome to African-Americans. Susan started making an effort to say hello when she saw Carol, and eventually they acted as if nothing had happened. The BlackBerry incident—it probably goes without saying—was never discussed.

Another story: Dennis, 26, teaches math in a Kensington school. His first year there, fresh out of college, one of his students, an unruly eighth grader, got into a fight with a girl. Dennis told him to stop, he got into Dennis’s face, and in the heat of the moment Dennis called the student, an African-American, “boy.”

The student went home and told his stepfather. The stepfather demanded a meeting with the principal and Dennis, and accused Dennis of being racist; the principal defended his teacher. Dennis apologized, knowing how loaded the term “boy” was and regretting that he’d used it, though he was thinking, Why would I be teaching in an inner-city school if I’m a racist? The stepfather calmed down, and that would have been the end of it, except for one thing: The student’s behavior got worse. Because now he knew that no one at the school could do anything, no matter how badly he behaved.

Confusion, misread intentions, bruised feelings—everyone has not only a race story, but a thousand examples of trying to sort through our uneasiness on levels large and trivial. I do, too. My rowhouse in Mount Airy is on a mostly African-American block; it’s middle-class and friendly—in fact, it’s the friendliest street my family has ever lived on, with block parties and a spirit of watching out for each other. Whether a neighbor is black or white seems to be of no consequence whatsoever.

Yet there’s a dance I do when I go to the Wawa on Germantown Avenue. I find myself being overly polite. Each time I hold the door a little too long for a person of color, I laugh at myself, both for being so self-consciously courteous and for knowing that I’m measuring the thank-you’s. A friend who walks to his car parked on Front Street downtown early each morning has a similar running joke with himself. As he walks, my friend says hello and makes eye contact with whoever crosses his path. If the person is white, he’s bestowing a tiny bump of friendliness. If the person is black, it’s friendliness and a bit more: He’s doing something positive for race relations.

On one level, such self-consciousness and hypersensitivity can be seen as progress when it comes to race, a sign of how much attitudes have shifted for the better, a symbol of our desire for things to be better. And yet, lately I’ve come to fear that the opposite might also be true: that our carefulness is, in fact, at the heart of the problem. (continue reading)